7 Steps to Giving a Great Speech

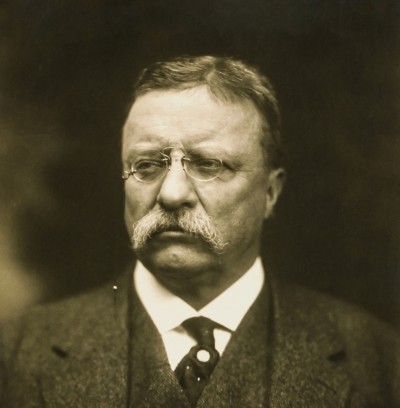

Post Views 19If you’re nervous about public speaking, consider this: On October 14, 1912, a would-be assassin shot presidential candidate Theodore Roosevelt in the chest just before he was to deliver a campaign speech in Milwaukee. Roosevelt chose to give his address anyway. With a bullet lodged near his lung, TR put on a clinic in public oration. He spoke for more than 80 minutes, albeit at a slightly lower volume than usual (“I have just been shot,” he explained to the sympathetic crowd). Moreover, that bullet hit a copy of the text Roosevelt had prepared, damaging it and forcing the candidate to speak from a general framework of ideas rather than from his prepared notes. No problem. His speech was a grand success, and afterward, Roosevelt walked to the hospital for treatment. So what’s the worst that could happen to you? The truth is that giving a great speech is eminently manageable, particularly if you pay heed to a few crucial nuggets of wisdom.

1. Short Is Sweet

You’ve probably heard of Lincoln and his two-minute Gettysburg Address. You probably don’t remember Lincoln’s opening act that day, the famous orator Edward Everett, who spoke for nearly two eye-glazing hours. The lesson: the shorter, the better. “Keep it to 20 to 25 minutes, tops,” says Peter Robinson, who left his speechwriting post in the Reagan White House to get his MBA at Stanford. “Keep your goals in mind,” says Mickey Sherman, criminal defense lawyer and CBS legal analyst. “When I’m in court, I can’t be as entertaining as on TV. I have one purpose and that’s to accomplish a specific goal: to better the position of my client. It’s not the time to show what kind of legal scholar you are.”

2. Dramatic Flair

The key to restraint lies in the writing process. “When you write the speech, start with a premise that can be captured in one sentence,” says author and corporate speech trainer Patricia Fripp. “Then move on to answering the how and the why of that premise.” If you begin with the premise that a more diverse law firm can be better for the bottom line, then back it up with nuts and bolts. Be substantive, clear, and – most of all – memorable. Keep in mind: People remember a good story better than they remember a good set of statistics. “It’s a dramatic model that gives a frame for your message,” says Fripp. In other words, blather on about the number of associates making partner at the firm over the last five years and you guarantee soporific incomprehension. Tell a story about one associate who, despite obstacles and hurdles, made partner before age 40 and you place yourself in the company of such rhetoricians as Abraham Lincoln and Jesus.”Every effective speech has to have an emotional arc that draws you in,” says Eric Liu, a former speechwriter for President Bill Clinton.

3. Skip the Jargon

Whatever the subject, keep your language clear. A major no-no: legal jargon. If you’ve got the urge to wax on about the impossibly complex ins and outs of an admiralty case, quash it – unless you want to be an associate for the rest of your life. “Don’t use words with more than three syllables, and never make people feel like you’re in love with the sound of your own voice,” says Sherman. “Jargon decrease the higher up on the ladder you go,” says Robinson. “If you can’t explain a term to a 15-year-old, don’t put it in your speech.”

4. Don’t Recite

In most cases, you shouldn’t read your speech sentence by sentence: You’ll sound like a stiff fourth-grader reciting an encyclopedia-cribbed report on the Platypus. Instead, speak from a sequential outline of major themes, phrases, and keywords. “Clinton looked at speeches the way a jazz musician looks at chord charts,” says Liu. “It gives you the key, the chords, the beats, which you riff over.”

5. Beware the Gag Reflex

No matter the mood, don’t open with a joke. “Tell a clichéd joke at the outset and anything you say afterward will seem just as trite, regardless of how smart it is,” says Fripp. Instead, start your talk with a question or a problem, a surprising fact or premise. “You need to raise the stakes by posing a dilemma, then move toward a resolution,” says Liu. Invoke a famous quote or piece of conventional wisdom, then prove it wrong with a startling story. Start with the partner faced with the dilemma of an obnoxiously aggressive firm attorney who still bills more hours than anyone else – anything but the one about the farmer’s daughter. Humor isn’t entirely off-limits, as long as it arises from the specific context of your speech and your audience. Just check the shelf life of all jokes and anecdotes to make sure they didn’t expire in 1953.

6. Ease Tensions

More subtle ways to defuse nervousness at the lectern: Speak loudly (about 150 percent of your normal volume), and move around a little. Sure, that second suggestion may go against the advice of your middle school elocution teacher, but motion diffuses tension. Done naturally, it’s also a great way to illustrate a point. “If you’re saying, ‘I was walking in Golden Gate Park yesterday,’ go ahead and move for emphasis,” says Fripp. Also, when you gesture to stress a phrase or a conclusion, remember to do it more broadly than you would in everyday conversation or the people in back won’t even notice.

Similarly, eye contact – or at least the illusion that you’re making it – is essential to connecting with an audience. A good rule of thumb: Make eye contact with a person for one whole sentence at a time, and then move your gaze elsewhere. You can also sweep the room with your eyes, but don’t do it shiftily, as though you’re looking for the open bar or an escape hatch. Slow down: Any quick motions – running your hand through your hair, stooping to pick up a dropped pen – will seem exaggeratedly jerky and nervous. That’s especially true of your vocal cadence: If you find yourself talking too quickly, take a slow sip from a glass of water.

7. Close Strong

When it’s time to end your talk, avoid hackneyed phrases like “In conclusion …” And don’t ever just gather your papers with a few taps and say, “Well, that about sums things up.” If you opened with an anecdote, you may want to finish it or return to it from a different angle: Maybe that obnoxious attorney learned some manners. End on a positive note. “If someone who hears you speak is asked what the talk was about, he should be able to sum up your point in one sentence,” says Fripp. To that end, find a quote, or an analogy that summarizes your presentation and hangs in the air during the applause. Thank the audience. Then look for that open bar.

By: Harrison Barnes, CEO of Granted

7 Steps to Giving a Great Speech by Harrison Barnes

How to Ask Your Boss a Touchy Question

How to Ask Your Boss a Touchy Question  7 Deadly Sins to Avoid If You Don’t Want to Become Your Own Worst Enemy

7 Deadly Sins to Avoid If You Don’t Want to Become Your Own Worst Enemy  Can Graduate School Help You Get Ahead?

Can Graduate School Help You Get Ahead?  The Importance of Teamwork at Work: How to Be a Team Leader

The Importance of Teamwork at Work: How to Be a Team Leader  Changing Careers: Should You Change Careers?

Changing Careers: Should You Change Careers?  Happy 2010!

Happy 2010!  Top 10 Tips for Changing Careers

Top 10 Tips for Changing Careers  Which Celebrities are Police Officers on the Side?

Which Celebrities are Police Officers on the Side?